“What if the Middle East was simply called West Asia?”

The first time I asked this question, I was in college. My friend from Bahrain and I were looking at a world map, and I asked her: “If people from the Middle East were labeled Asian, do you think we would treat them differently?”

As is the case with most questions we ask in our late teens and early twenties, it did not occur to me then that this question had been asked by others many times before.

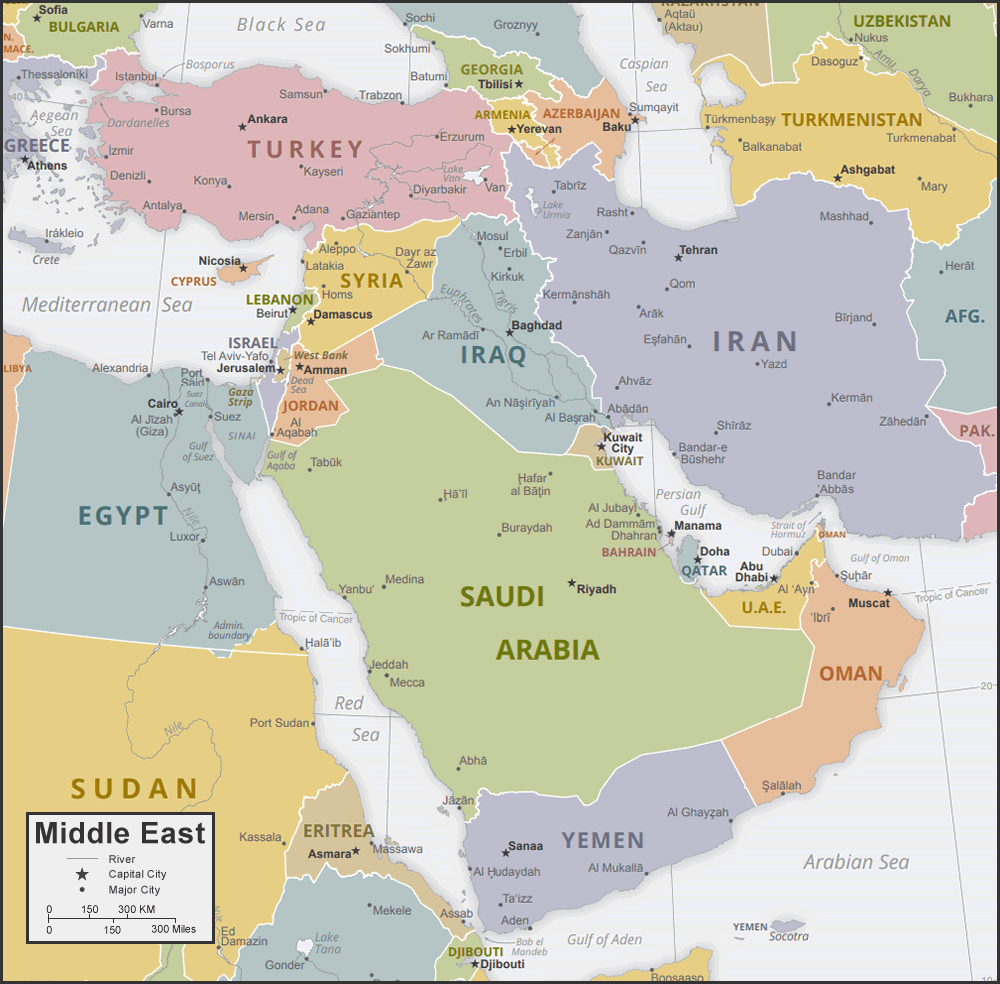

Back then, I didn’t know that the very term “Middle East” was an Anglo-centric creation that described an entire region of the world in relation to Europe due to its usefulness in perpetuating British colonization of India. I wasn’t aware that India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, proposed renaming the region “West Asia” as early as 1934—recognizing the imperial roots of the term years before decolonization swept the region. I had no knowledge that scores of scholars have argued for renaming the region West Asia and Southwest Asia for decades—because they too understand how colonialism lies dormant in language, subtly sculpting how we see the world around us against our own will.

No, back then, we stared together at the two-dimensional world map, the arbitrary oranges and yellows and reds and greens of different countries blending—the possibility of expanding the American definition of Asia novel and jarring. Because if the Middle East became part of Asia, what would that mean for our identity?

—

“What does it mean to be Asian American?”

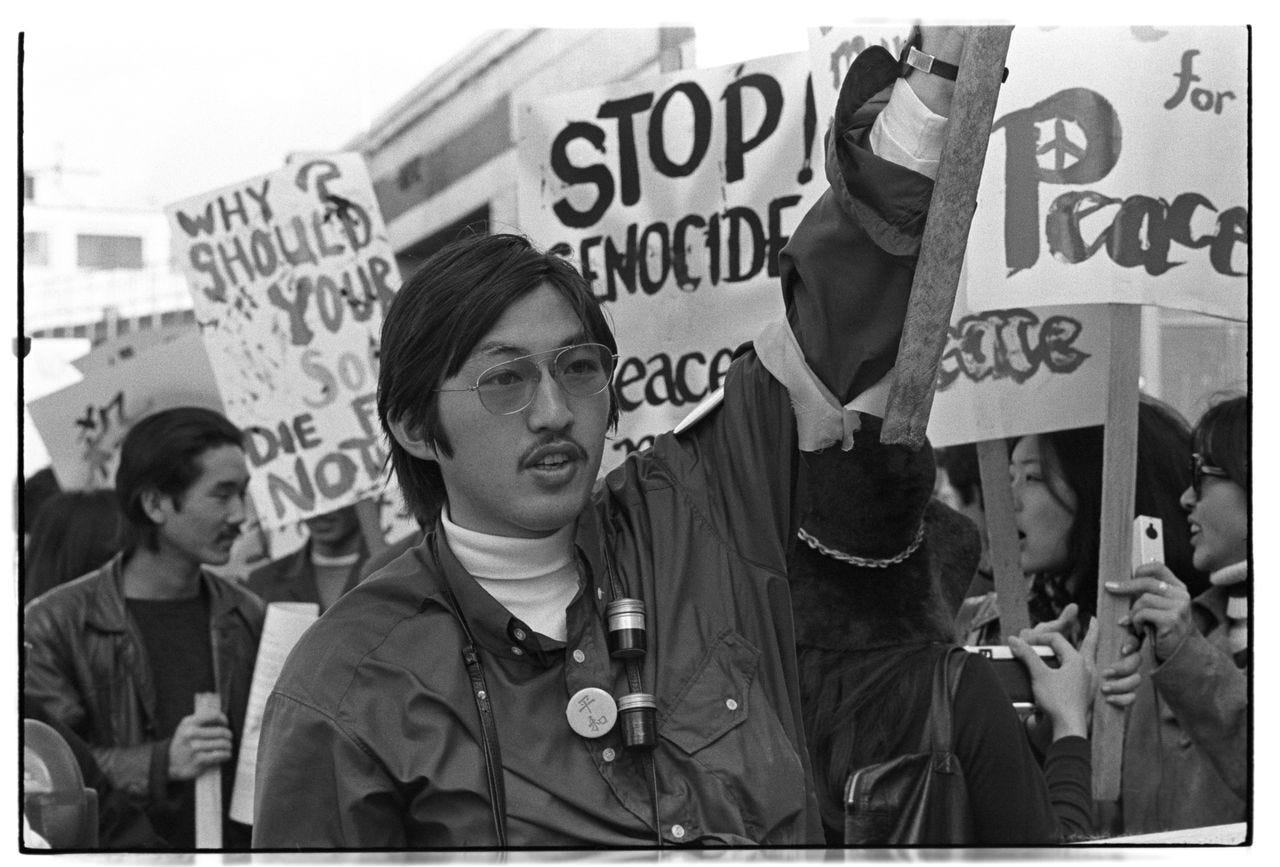

At the beginning, it meant rejecting the “Orient.” To become Asian Americans, we needed to reject our portrayal in this country as Orientals, as fetishized and exoticized “others”—the primary argument in Palestinian Scholar Edward Said’s groundbreaking Orientalism. But as Viet Thanh Nguyen writes for The Nation in “Palestine Is In Asia,” our rejection of the Orient was largely appropriated from Said since “his book did not for the most part deal with America’s Orient…which is to say, East and Southeast Asia. Said addressed Europe’s Orient, located in what Europeans called the Near East and the Middle East…West and Southwest Asia.”

Given the pronounced silence around Palestine we continue to see within the East, Southeast, and South Asian community in the US, I feel compelled to ask my fellow Asian Americans: Would your stance change if we saw Palestinians as Asian? If we understood that the foundations of our Asian American identity are rooted in Palestinian resistance?

For much of my life, describing myself as Asian American felt right. I am, after all, both Taiwanese and Indonesian, two countries 1,756 miles and countless seas apart that can only be brought together by the vague overgeneralization a term so broad can hold. But as Nguyen points out, truly recognizing the vastness of the Asian continent—and how we’ve come together as “Asian” to find common ground in this settler colonial country—puts into question the sheer absurdity of the term itself.

Asia is the world’s largest continent, extending from Turkey to the west and Japan to the east, from Kazakhstan to the north and the Maldives to the south and Indonesia to the southeast. Israel and Palestine are in Southwest Asia. The geography opens a critical question: What if they, Israelis or Palestinians, identified as Asian and eventually Asian American?

If the question seems absurd, that is because claiming affiliation via Asia or the Orient itself, so enormous and heterogeneous, might already seem absurd. And yet the absurdity has been outweighed by the tragedies of racism and colonialism, which have driven numerous people and their descendants from one corner of Asia to ally with people and descendants of a different corner. Are these alliances any more absurd, or less tragic, than the Jews and the Chinese of Los Angeles, of Haifa, of China, finding common ground?

- Viet Thanh Nguyen, “Palestine Is In Asia”

We can see this very dichotomy play out in the way that Asians in America have fought to broaden the definition of what is commonly accepted as “Asian American” for decades. First, we pushed to expand the term’s stereotypical Chinese, Japanese, and Korean connotations to include Southeast Asians (like Indonesians, Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Thai). Then, South Asians (from countries like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh) were slowly recognized as Asian Americans.

Would it really be so outlandish, then, to broaden our definition once again to include West and Southwest Asia—the only parts of the continent still not accounted for in our Americanized definition of Asian identity?

—

“If people from the Middle East were labeled Asian, do you think we would treat them differently?”

I want to know: Would it be easier for Asian Americans to love them? To empathize with their struggle? To see them as human beings in place of terrorists? Would we cry “Stop Asian Hate” when we witness their violence? Would we shame our government representatives and withhold our dollars until we created change?

We create understanding largely through parallels, and many have already drawn the lines between Palestine and American imperialism in Vietnam. But is the comparison alone not enough? Must they identify as Asian for our self-interest to benefit them—even though everything we’ve fought for in this country comes from the work of a Palestinian revolutionary?

The question is inescapable: Would we still so proudly label ourselves Asian American if being “Asian” made it more difficult to “successfully integrate” into the US? "The good other is willing to die for the West, while the bad other is willing to be killed by the West,” writes Nguyen. “For Asian Americans, the outside is Asia. We fear being associated with any part of Asia when that part clashes with the United States.”

I wonder if our solidarity has any meaning at all if it can be so weak.

—

“What if the Middle East was simply called West Asia?”

I want to know: What would we do then?

INCREDIBLE, thank you for this. for wondering, and making me wonder